No one in higher education will escape the urgent debate about the role of AI in teaching and learning. But what, specifically, does it mean for teaching conversation analysis? Is there anything about the peculiarities of generative AI that could actually be useful? Bogdana Huma, Nthabiseng Shongwe, Borbála Sallai, all from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, take us through an intriguing experiment which tries to answer that question. Along the way, Bogdana links to an intriguing AI-generated podcast of a ROLSI article, which is a fascinating artefact in its own right, and a novel teaching resource.

In academia, the availability of generative Artificial Intelligence (genAI) through platforms such as ChatGPT, Claude, or NotebookLM has started to transform how we work, how we teach, how we learn, and even how we think. When we seek information, it is tempting to turn to these platforms, even though we know that their answers can be unreliable. Referred to as “hallucinating”, “falsifying”, or “fabricating”, making up facts is genAI’s well-known Achilles’ heel for which there is no remedy in sight.

In this blog post, we report on how we can turn genAI hallucinations from a problem to a resource in teaching conversation analysis (CA) while also stimulating critical engagement with genAI outputs.

Teaching CA and AI literacy skills with NotebookLM

Explaining CA’s unique take on language and social interaction, whether to professionals or university students, can be challenging. Previous ROLSI blogs provide excellent tips for engaging novices, such as using analogies, showing clips from TV shows, or letting learners discover CA principles for themselves. But once convinced of CA’s value, how do we help learners to climb the steep CA learning curve? The educational activity “Fact or Fiction: CA Edition” described below aims to support advanced CA learners to fine-tune their understanding of complex CA principles and ideas. As a bonus, it also supports learners to engage with genAI in a critical and productive way by increasing their awareness of and ability to recognise AI hallucinations.

The Teacher’s Perspective

I designed an activity I called “Fact or Fiction: CA Edition” and asked a group of master’s students, including Nthabi and Bori, to complete it as part of the course Medical and Healthcare Interactions in the Dialogue, Health, and Society master’s track at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Their task: Read a paper, then listen to an AI-generated podcast based on it.

The coursework assignment required students to read a CA paper first (Parry & Barnes, 2024), and then listen to an AI-generated podcast supposedly describing it to a wide audience. The students’ task was to answer this question: does CA’s unique approach to language and social interaction come across correctly in the AI-generated podcast?

To no one’s surprise: it doesn’t.

Taking advantage of the AI podcasts’s failings.

Now that I had an interpretation of a CA paper (albeit generated by AI), I could invite the students to do a number of useful things with it. For example, if you’re aiming to stimulate careful reading, students can be asked to identify key ideas that the podcast conveys accurately as well as inaccurately. Alternatively, if you’re aiming to support students to comprehend CA’s unique perspective, then the task can focus on uncovering aspects of CA that are misrepresented. The activity can be completed in class (as seen in Figure 1) or at home, either individually or in small groups. Importantly, always follow up with an in-class discussion in which you can clarify some of the trickier CA concepts or principles to ensure that students have correctly grasped them.

Figure 1 Photo of students completing “Fact or Fiction: CA Edition” in class

Hallucinating CA

How well, in fact, does AI deal with a real CA paper? To exemplify, we’ll draw on the state-of-the-art review article Conversation-Analytic Research on Communication in Healthcare: Growth, Gaps, and Potential from ROLSI’s special issue on healthcare interactions.

The podcast was produced with Google’s genAI-powered platform NotebookLM which generates surprisingly realistic two-speaker audio overviews of user input, such as PDFs of research articles. It really is as easy as uploading the PDF to the site, and pressing a button; a few moments later, a sound file appears which you can download and play. For anyone who has not heard this kind of thing before, you will be struck by the apparent naturalness of the talk – the in-breaths, repair, overlap and general “feel” of real talk. Only the occasional stumble will give it away, and extended listening will start to reveal repetitive patterns and formulas.

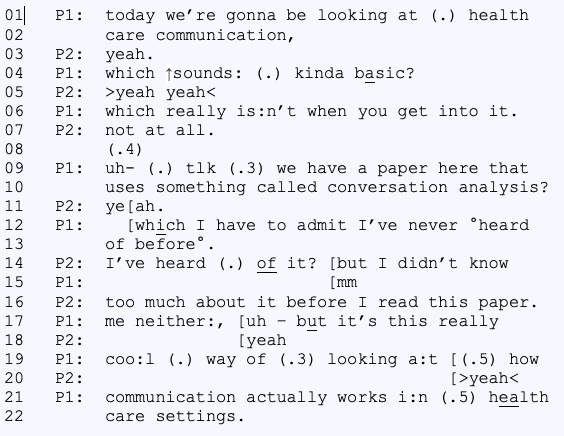

Want to hear what it sounds like? You can listen to the whole podcast here (click to play). For a sense of the style of the talk, here’s a brief snippet of transcript.

Podcasts vary in length and coverage, sometimes zooming in on tiny details in the papers and other times bringing in ideas that have little or nothing to do with the content of the article. The podcast about Conversation-Analytic Research on Communication in Healthcare: Growth, Gaps, and Potential has a promising start. The hosts describe CA as a “really cool way of looking at how communication actually works in healthcare setting” because “it’s like you’re listening in on doctor-patient conversations, but with like a super high-powered microscope”.

The AI podcasters manage to correctly convey some of CA’s methodological procedures such as the focus on the details of language-in-use, but then miss the mark by glossing over them as “little non-verbal cues” – which starkly misrepresents CA’s treatment of embodied resources.

From there on, it’s only downhill: one of the hosts claims that the review article “is really opening up this whole new world of understanding about how culture and context shape our communication in healthcare”, which is clearly at odds with CA’s take on (cultural) context as endogenously produced and managed. All of this in just the first four minutes. Plenty of material there to encourage the students to compare what they heard in the podcast with what they read in the original article – and with what I’ve been telling them in the lectures. There’s something about the plausibility of the podcast that makes the contrast sharp and meaningful, making the students more appreciative of what conversation analysis does actually mean.

Final reflections on using genAI in teaching CA

GenAI platforms have multiple educational applications. Many students use NotebookLM to organise study notes and revise for exams. Also, some educators claim that the podcasts may increase accessibility for diverse learners who benefit from listening rather than reading; but these claims have not yet been backed up by solid evidence. Furthermore, given that podcasts are littered with hallucinations, we seriously doubt they can substitute original materials.

When it comes to CA, which has a unique approach to social interaction, it’s no surprise that genAI struggles to provide accurate information. We don’t need to peek inside the “black box” of ChatGPT to recognise it’s been mainly trained on texts with a bias towards cognition. So, instead of asking ChatGPT to, for example, define a technical CA term, learners would profit from consulting the Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL. Both are only a few clicks away, but only the latter provides reliable information that is transparently referenced.

At the beginning of each course, I (Bogdana) ask students if they have ever used genAI. For two years now, the answer has been almost unanimously yes. This strongly suggests genAI is here to stay in our classrooms, and in our lives. While I have mixed feelings about using genAI, especially due to privacy and environmental concerns, still I think it’s important for students to learn how to work with genAI in a responsible and critical manner.

Reference

Parry, R., & Barnes, R. K. (2024). Conversation-analytic research on communication in healthcare: Growth, gaps, and potential. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 57(1), 1-6.