Conversation analysis offers a great deal to those trying to improve how to communicate with people with disorders of language. It’s not always easy, and practical obstacles keep getting in the way: Isabel Windeatt from Nottingham University gives us a lively account of what it’s like to collect and analyse data on a ward for older people .

I’ve been working closely with front-line healthcare professionals in my role on the VOICE2 study, a conversation analytic study of communication between staff and people living with dementia who are in hospital. I want to share the benefits of collecting data and sharing preliminary CA analyses with healthcare professionals, as well as some of the challenges, in the hope that others will find solutions to collecting data in challenging environments, and be encouraged to involve healthcare staff during the analysis.

The healthcare professionals I refer to are ward-based staff who are unfamiliar with CA and don’t undertake research. I also work with clinical academics who are familiar with CA and recognise its value in healthcare research – they’re the reason I have a job.

Recruiting healthcare professionals on acute hospital wards

The data I’ve been collecting involve naturally occurring interactions on UK acute hospital wards between healthcare professionals and patients living with dementia who were prone to distress, recorded at times when distress was anticipated to occur or had previously occurred.

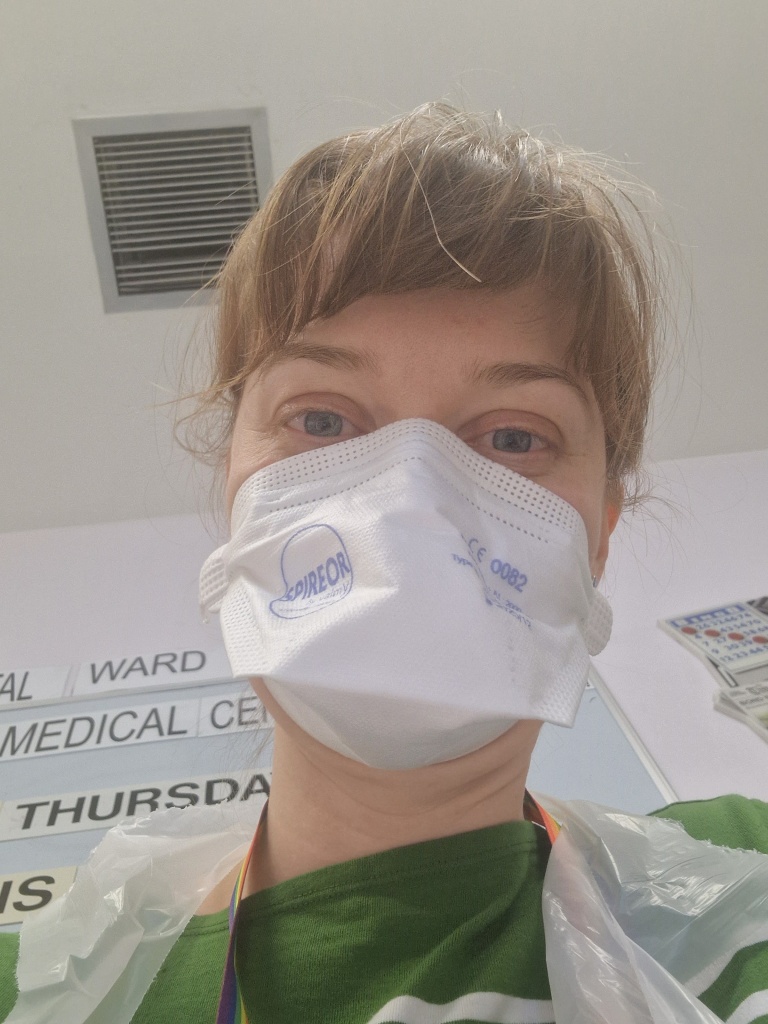

First, I had to get familiar with the scene. This required a traditional ethnographic immersion in the data collection process. From March to September 2022, myself and 3 other researchers spent 6 months on acute older persons’ hospital wards to collect almost 10 hours of video and audio data.

Much of that time was spent finding patients for the study and recruiting willing healthcare professionals from amongst the healthcare assistants, doctors, nurses and therapists working on the wards. I had to try to build the trust of staff by talking with them, getting to understand their roles, and generally becoming a bit of a ward fixture so that staff could get to know the person behind the camera. Staff were always busy. I was careful to introduce myself to as many staff as possible and explain what we were doing on the ward – it’s a bit intimidating having someone unfamiliar turning up at your workplace with a large folder and recording equipment, watching and taking notes on what you’re doing!

Start at local manager level. Initially, we presented at a Ward Managers’ team meeting so that those running the wards knew who we were and what we were doing on their ward. We would also approach Ward Managers when first arriving on a ward, recruiting them to take part in the study as this set an example for other ward staff, encouraging them to sign up as well. The Ward Managers recommended staff who might be comfortable in front of the camera. We also presented at Medics’ team meetings and attended board round meetings on the wards. This networking offered our first recruits on each ward and, having broken the ice, recruitment would snowball as talk about the study passed between healthcare professionals.

Recruiting people on the fly

That’s not to say we didn’t have to do our fair share of ‘cold recruitment’. Many healthcare professionals who signed up were those we had to pitch the study to from scratch. For this, having a polished ‘elevator pitch’ was useful, and helped with any nerves about distracting a healthcare professional at work, especially as reading a 10 page long study information sheet didn’t make signing up all that appealing. This pitch would often get interrupted by staff having to dash off to attend to a patient, or a patient might instead stop me – either thinking I was their relative, falling asleep on me, or just wanting to chat. I’d find the healthcare professional later, if possible, to resume our talk when there was a brief moment of calm between patient-focussed tasks, such as when they were watching over their assigned bay.

Not everyone wanted to be part of the study. Many healthcare professionals didn’t feel comfortable being filmed and I even received one unmitigated ‘no’ without any delay or account. Fascinating interactionally, but also mildly disheartening. However, I found many staff were still happy to chat about patients who might be suitable for the study, giving me valuable information on distress patterns of patients I was going to speak to. They would also share their own experiences of dealing with patient distress, and cajole other healthcare professionals to take part.

We were careful to emphasise that staff did not have to take part, that they could stop at any time, or say ‘not today’ to us. For those that did take part, our two stage consent process, in which we took consent for future use of video material after they had viewed the recording, meant that they could decide after the recording how they would like it to be used and who would see it. 96 staff allowed us to take up their already limited time by agreeing to take part, a testament to their interest in improving care and demonstrating a selfless nature.

Getting immersed in data collection

A lot of the time, the patient being filmed would wander about the ward, or staff would shifting positions to do their work. So I had to navigate around the scene, trying to keep the interaction on screen, but also keeping in mind patient dignity by covering the camera lens if the situation demanded it.

Seeing how staff handle difficult moments

It was very illuminating collecting data in this way. I got to see first-hand what life on the wards was really like for staff. In my first week, a patient I was assessing the capacity of, switched from being quiet and calmly spoken, to yelling at me that he wanted to murder someone. Staff suggested that it was best just to ignore this behaviour and I had many pleasant chats with this patient after this occurrence. In the few months I was there, I’ve witnessed patients throwing walkers and anything else to hand at staff, fighting each other, and trying break the ward doors open to escape. One of my most memorable occurrences of distress, was a patient who, at the time of his distress, believed staff on the ward were a gang who had taken his young children. This gentleman had taken another patient’s shoes thinking they were his, then used them to hit a ward window, resulting in a resounding crack and broken window. Staff were amazing in all of these circumstances, responding calmly, and with understanding, to patients who couldn’t always help their disinhibited behaviour.

The biggest benefit of being so immersed in the data collection, was that I was able to

learn about the context of the interactions that I would otherwise have missed out on. As the focus of our research – distress – could be fleeting, being on the ward for long periods allowed us to collect field notes to be used alongside the recorded data, something not always done with CA (Mondada, 2012:33; ten Have, 2007:88). Much of our data is better understood in the light of the context of the patients’ prior distressed episodes which these field notes provide.

Hit and miss with data collection

Data collection was time consuming: on some days no data collected, and others more time was spent standing around observing, or waiting for a healthcare professional to undertake a task with a recruited patient. On these long days I was very grateful to the wards that had sofas in their bays.

It was a tiring but valuable process, and being on the wards for these extended periods allowed me to learn some of the healthcare jargon and contextual information that I lacked as non-clinical analyst. It’s also given me a better appreciation of healthcare professions’ concerns, an understanding of their roles, and of what our research is being done in support of.

Sharing analyses with other healthcare professionals

I’ve since shared some work-in-progress with other healthcare professionals at monthly project management group meetings and with a community based team in another NHS Trust. Online meetings make doing this sort of dissemination much easier. The analysis I presented wasn’t finished (is it ever?), and I didn’t have any concrete findings to show them. They understood that and didn’t push me for any. What they did do, was offer their own perspective on the data as healthcare professionals. Presenting here offered valuable insights on the analyses and new perspectives into the data that I otherwise may have missed. It reminded me to take a step back from the data and consider why we are doing this research.

Final thoughts (for the moment). A commendable goal of any research is to have the findings from it put into practice and travel beyond academia. The point of research is to learn, not just for the sake of learning (which is still a valuable endeavour), but to also apply that learning to the real world. Working and sharing work at each stage with healthcare professionals is an essential part of the research process to ensure that we have a practical impact with our findings. Building a network of relationships with front-line healthcare professionals and having ongoing discussions with them helps to ensure that our work is relevant and applicable and we should strive to ensure this becomes an essential part of the research process whenever possible. Personally, I’ve found it by turns exciting, frustrating, and occasionally emotionally challenging – and utterly fascinating throughout.

References

Mondada, L. (2012). The Conversation Analytic Approach to Data Collection. In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (eds J. Sidnell and T. Stivers). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118325001.ch3

ten, H. P. (2007). Doing conversation analysis. SAGE Publications, Limited.