CA researchers who approach institutions like the police can get responses which vary from warm encouragement to outright rejection, with most cases falling somewhere in between. It’s up to the researcher to establish good relations with their contacts, abide by their requirements, and be sensitive to the legal and technical constraints that box in the recordings. But if they do come away with usable data, that can be an exceptionally valuable source of information about how the police work. Here, Emma Tennent reports on the process by which she and Ann Weatherall found the data they used in their recent ROLSI paper on person reference in police calls.

How do the police deal with people who call in for help?

Ann Weatherall and I wanted to study what barriers people faced in calling police emergency and non-emergency lines about gendered violence. But the New Zealand police had never previously released call-recordings for research. The process of getting permission was a long one, with much to learn on the way; but we succeeded, and we’re delighted to have our first article based on that data published in ROLSI. We hope that this description of the process might help as a guide to the kind of ups and downs this kind of applied research involves.

Ground work.

Negotiations with Police to access the call recordings took more than 18 months. Thanks to a colleague in forensic psychology who had productive working relationships with Police, we had a warm introduction to the research co-ordinator at the Evidence Based Policing Centre (EBPC). She explained to us the processes through which external researchers can apply to access police data. Discussions with the research coordinator led to us getting initial feedback from the Police’s Chief Privacy Officer and the Chief Information Security Officer. We were then able to pre-emptively address their concerns in our university ethics application and our proposal to the police research panel. The groundwork was worth it because both were approved straightforwardly.

One of the main ethical issues is that Police record calls without explicitly informing callers. Exemptions under New Zealand’s Privacy Act (2020) allow this data to be used for research purposes if it will not be published in a form that could identify individuals. Given the small size of New Zealand, Police were particularly sensitive to the possibility of identification.

In a recent conversation reflecting on the process, a manager at EBPC highlighted our engagement with Police prior to formally submitting our research proposal as a key factor in the project’s success. This early consultation allowed us to design the research in a way that was feasible for Police while accommodating their privacy concerns.

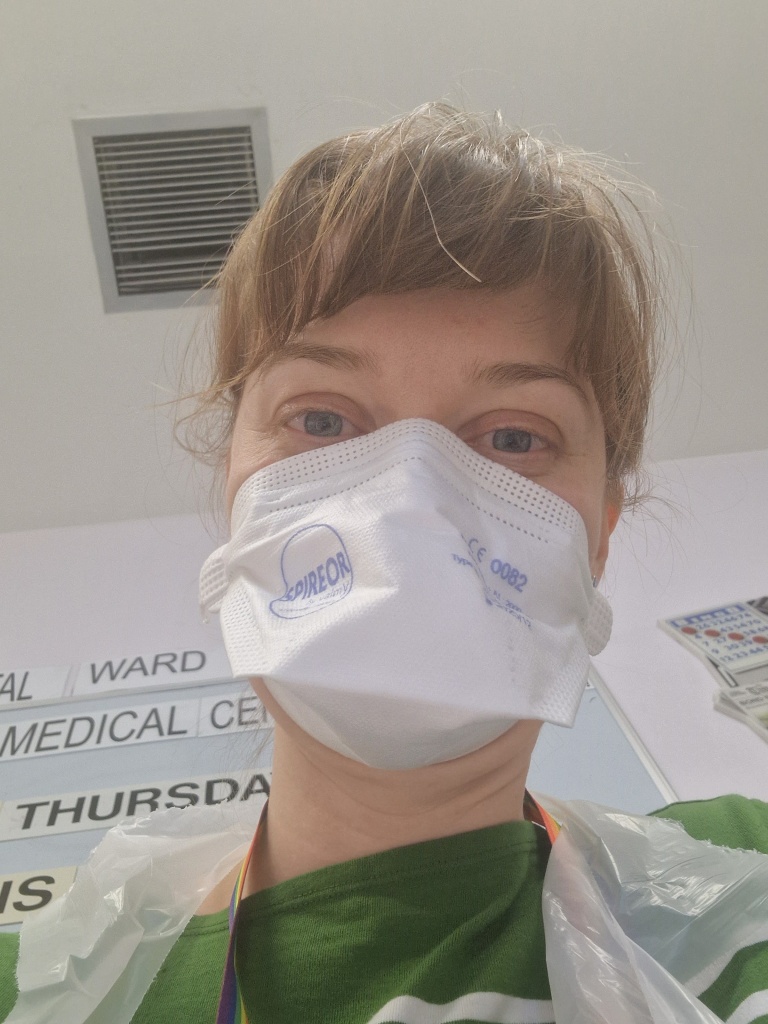

Police were easily able to produce a random sample of calls during our target period (February and April 2020 – before and during the first lockdown). Permission to work on site at Police headquarters required agreeing to a formal criminal record check. Once we were vetted, the manual de-identification of the sound files could begin. This was an incredibly time-intensive process as the sample was close to 35 hours long. We listened to each sound file in real time and replaced information like names, addresses, and phone numbers with white noise. At the same time, we made an initial log of the calls including their length and a gloss of the reason for calling. The de-identified sound files were then checked by a member of Police before being released to the research team to take off-site for transcription.

During the months we were onsite, the emergency communication centre was beset by severe staff shortages due to the ongoing challenges of the pandemic. The staff member appointed to approve our redacted sound-files was redeployed and finding a replacement took time. We also faced challenges taking the approved de-identified data offsite. Our original plan to use a password-protected USB had to be reworked after we discovered police machines did not allow copying data to USBs for security reasons. Thanks to our contacts at EBPC and the IT team, we found a work-around that involved encrypted data being uploaded to a secure Google Drive that we could then download and store on a secure university drive.

A treasure-trove of important data.

The data are fascinating and there is a wealth of analytic lines of inquiry to pursue.

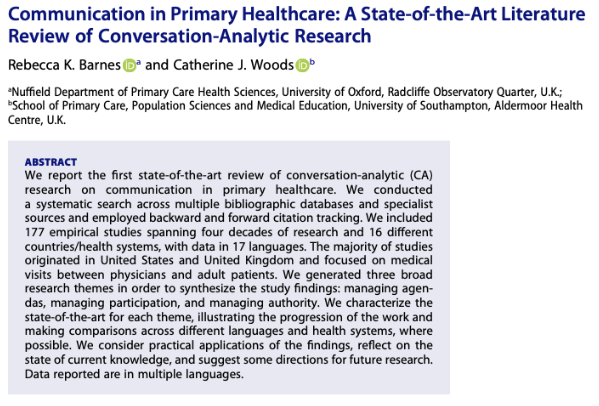

Our first paper (published in ROLSI) examines the technical practice of person reference in 50 emergency calls pre-covid. Our broader project aims to re-specify ‘barriers to help-seeking’ and document how Covid lockdown shaped calls for help. Identifying instances of good practice can inform training for call-takers and ultimately work towards improving experiences for those who call police in times of difficulty and danger.

Along with research assistants and thesis students, we have been developing transcripts, presenting at data sessions and conferences, and building collections, as well as publishing the ROLSI paper whose abstract is shown below. The analytic work is on-going so watch this space!