One of the most adhesive binding agents for researchers in EM/CA is the weekly get-together, whether to pore over data or to discuss the week’s chosen reading. Some reading groups and data sessions come and go, and some have an admirably long and unbroken history. One of the latter is the Ethnomethodology Reading Group originally based at Manchester University. Here, Phil Hutchinson delves into its past and looks forward to its future.

Every Wednesday, at 10am UK time, a familiar pattern unfolds on my laptop screen. I open MS Teams and watch as people log on from across the globe. Most have the week’s PDF open on a second screen. For the next three hours we do something simple but increasingly rare: we talk, in detail, about a piece of ethnomethodology, conversation analysis, or related philosophy that everyone has read closely. This is The Ethnomethodology Reading Group.

The roots of the group go back to Manchester UK in the late 1960s, when Wes Sharrock began a weekly discussion group that soon became a fixture: students, colleagues, and visitors knew they could just turn up. In fine discussion-group tradition, the name never quite captured what went on in the group. Rather, the reading followed the distinctive predilections of the Manchester EM/CA group and ranged widely: classic EM/CA, Wittgenstein, Wittgensteinian philosophy, Ordinary Language Philosophy, and Phenomenology.

Going online

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, Alex Holder and I moved the meetings online. We set up a Google Drive folder for distributing readings, met first on Zoom and then on Teams. The basic format remained the same, only now we were online and the meetings grew from two hour sessions to three. The readings are agreed collectively: sometimes week-to-week, sometimes by committing to working through “big books” chapter-by-chapter.

Since 2020 those big books have included Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, On Certainty and Last Writings on the Philosophy of Psychology, vol. 2; Garfinkel’s Ethnomethodology’s Program; Aron Gurwitsch’s Field of Consciousness; Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception; Frank Ebersole’s Things We Know; and Gus Brannigan’s The Use and Misuse of the Experimental Method in Social Psychology. We also spent a stretch with Jeff Coulter’s work, both to mark his death and to celebrate his writing.

In March 2023 we began what became a major joint project: we worked our way through Harvey Sacks’ Lectures on Conversation and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Big Typescript (TS 213) in alternating two-week blocks, returning to each in turn over the course of about two and a half years, and finishing with the final Sacks lecture in September 2025. Speaking for myself, that project has been one of the most rewarding intellectual undertakings in which I’ve been involved. It has strengthened my conviction that Sacks is a worthy heir to Wittgenstein and an extender of his ideas in innovative directions.

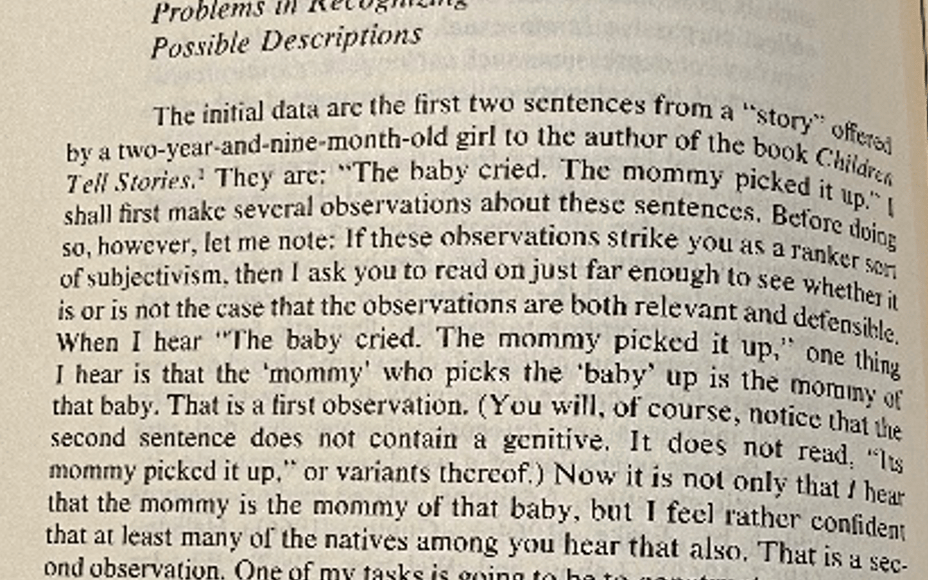

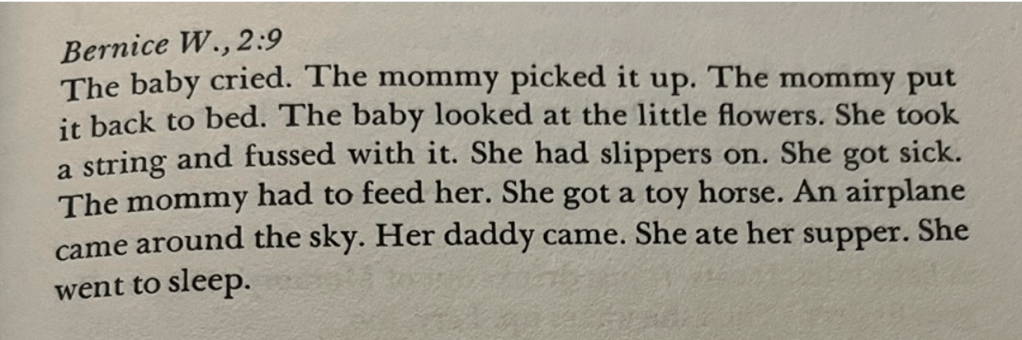

The Lectures on Conversation read to me like detailed implementations of what Wittgenstein called grammatical investigation: a refusal to be rushed into “theory”, a determination to stay with the ways members themselves use words, and a patient recovery of what competent speakers already know how to do. Set alongside the Big Typescript and Philosophical Investigations, CA staples such as adjacency pairs, repair, and recipient design, in addition to membership categorisation, begin to look less like empirical discoveries in need of explanatory theory, and more like reminders—perspicuous presentations of everyday practical know-how that is usually taken for granted.

Calm and gently reflective discussion?

Not always! One of the liveliest sessions came when we reached Harvey Sacks’ remarks on a passage from E. E. Evans-Pritchard in Volume I, Part III, Lecture 17 of the Lectures on Conversation—unlikely material, perhaps, for one of our more animated mornings, but so it proved. It quickly turned into a heated debate about how one learns from Peter Winch’s Wittgensteinian philosophy and his own reading of Evans-Pritchard. Several members of the group have written on Winch, and the discussion became sharp and somewhat heated, culminating in a rather theatrical exit by one member. For a moment several of us wondered whether we were about to re-enact the famous incident where Wittgenstein (allegedly!) threatened Karl Popper with a poker; but being on Teams, and with central heating having largely replaced coal fires in the UK, no actual pokers were available (though some present that morning report a plastic radiator bleed key being thrown at the screen).

There have also been mornings when we have had to confront our limits more quietly. I still remember opening Teams to a rather sparse collection of faces as we reached the more technical, mathematical sections of the Big Typescript. Those who turned up gamely tried to work through them together; we all struggled, but those who stayed the course were, I think, rewarded. …I think. Those sections of Wittgenstein cost us a few members, perhaps. Over the years there have even been a few breakaway groups—“splitters”, as we affectionately call them—when clusters of regulars have gone off to pursue more specialised readings (or just avoid Wittgenstein on maths).

Then there are the debates that re-emerge every few months and never quite resolve: to what extent are Garfinkel’s studies and Sacks’ analyses continuous with Wittgenstein’s and Ebersole’s grammatical investigations? Does it really matter, for practical purposes, whether we work with naturally occurring data or carefully staged examples? On mornings when those questions flare up, it sometimes feels as though we ought to have a glass case on screen containing a symbolic poker with a label reading: “In case of argument over naturally occurring data versus imagined cases, induction versus grammatical investigation, break here”.

Present and future

Since finishing Wittgenstein and Sacks, we have returned, for now, to a more episodic programme. We recently spent several weeks on Goffman’s posthumously published “Felicity’s Condition” followed by Emmanuel Schegloff’s 1988 “Goffman and the Analysis of Conversation”. Next, we plan to work our way through the contributed chapters in Hedwig te Molder and Jonathan Potter’s Conversation and Cognition. The rhythm of the group continues to oscillate between close engagement with EM/CA “classics” and forays into whatever new or neglected work participants suggest.

A global group

Moving online also reshaped who takes part, and from where. What was once a meeting whose membership was effectively restricted to those within commuting distance of Manchester is now genuinely global. Since 2020, the group has included participants logging in from Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, the UK, and the USA. The disciplinary range is also diverse. My own background is in philosophy, though I am now based in a psychology department. Other members come from psychology, communication and media, medicine and health, sociology, criminology, science and technology studies, geography and education. The group also includes a practising psychotherapist and several retired academics. That mix is part of what makes the discussions so rewarding: it pushes back against increasingly siloed academic disciplines and keeps EM/CA in conversation with the traditions that have shaped it and that it has influenced—but also, and perhaps more importantly, sustains EM/CA as a living tradition that is in conversation with contemporary concerns.

What, if anything, makes this group distinctive? One feature is the tempo and duration of the discussions. Three hours on a single text, week after week, is unusual in contemporary academic life, where reading and reflection are often squeezed into what is left after teaching, admin, and the latest institutional demands. Another is the way we allow EM/CA texts to be in live conversation with philosophy and phenomenology, without reducing either to “background theory” or methodological window-dressing. For many of us, ethnomethodology has long been understood as a kind of praxeological phenomenology; discussing Garfinkel and Sacks alongside Gurwitsch, Merleau-Ponty, Wittgenstein, and Ebersole has helped us develop that thought.

A place to think

Above all, the group has become a place where people who care about EM/CA, and about the things that shaped it, can think aloud together over time. People drift in and out as jobs, family life, and time-zones permit, but many have been attending for years. And although we are firmly in the tradition of discussion groups whose names no longer fully capture what they do, we have at least avoided one famous precedent: in all our years of sometimes quite vigorous debate, no-one has threatened anyone else with a poker… yet.