How does the criminal justice system in England and Wales accommodate witnesses or defendants who have difficulty with language? Only within the last twenty years has much thought been given to vulnerable people who struggle to understand and communicate, especially in unfamiliar settings. Now, the system does recruit help, and I’m delighted to invite Tina Pereira, trained in conversation analysis, to explain how she uses multimodality CA to help all parties cope with the demands of police interviews, enabling them to deliver ‘best evidence’.

Reader of this blog will hardly need reminding that human communication in everyday contexts is typically multimodal, and that embodied conduct i.e. interactions that includes physical objects, gesture, as well as spoken language, typically impart meaning in a communicative encounter. So it may surprise some that those latter channels have, until recently, been largely underplayed in the criminal justice system, which, traditionally, privileges text and speech. Think of legal documents, police interviews and the to-and-fro of the courtroom.

But some vulnerable people can’t easily cope with complex language. Many individuals with an intellectual disability struggle to understand and communicate through speech alone. But, on the other hand, they do have relatively better visual processing skills (Cherry et al. 2002). So there is a discrepancy between their greater competence with the visual and the historical bias towards using speech in the legal system and interactions in legal contexts (both at police interviews as well as at court). That is a state of affairs which is inconsistent with the concept of a fair trial referred to in Article 6 of the Human Rights Act (HRA 1998). This incongruity is one that I have been addressing in police investigative interviews, as a Registered Intermediary (RI), for over 15 years. How can CA help?

Intermediaries and communication aids

An RI, in England and Wales, is a communication specialist with a professional background in a communication related field (such as speech and language therapy), who has received additional training in legal processes. RIs are registered with the Ministry of Justice to provide specialist communication assistance between a legally defined VP and others in legal settings (Ministry_of_Justice 2024). The intermediary special measure (YJCEA 1999b) is covered under the Act referred to above, which also makes provision for the use of communication aids (YJCEA 1999a) i.e. material objects, drawing, writing etc, as resources, if their use can be justified in court.

I typically work on cases where a complainant has a diagnosis of Intellectual Disability, with children as well as adults. My role in that context is to firstly assess the VP’s specific and individual communication and interaction difficulties, make targeted recommendations in relation to the manner in which they can be interviewed (or cross examined in court) and then to provide contemporaneous assistance in situ.

Multimodality CA has significant benefits in the legal system, both for VPs whose visual processing skills are tapped resulting in more complete, coherent and accurate evidence, but also for the police and courts, who are thus able to understand the relevance of tapping the visuo-spatial-gestural modality.

A case study

In this case, a 13 year old VP with an intellectual disabiity and Autism was due to be interviewed by the police, putting forward an allegation of rape by her paternal grandfather. This was a case that would obviously need careful and sensitive questioning, and it would be important that the complainant be able to understand physical terms to do with proximity and contact, and temporal terms to do with sequence and narrative.

My assessment revealed difficulties in communicating positional (i.e., ‘behind’, ‘below’, ‘between’ etc) and orientational language (‘at right angles’, ‘next to’, ‘in front of’ etc) using speech alone. She also struggled to communicate a sequence of events, which was essential in describing the order in which the suspect had allegedly assaulted her. However, assessment also revealed strengths in understanding some time-related concepts ‘before-after’ (or ‘first-next’), as well as consistent awareness that miniature material objects could represent real concepts (Peirce 1893-1913).

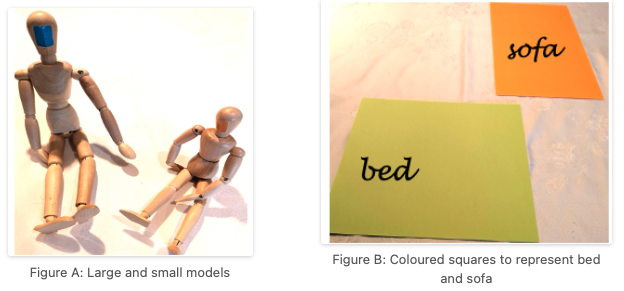

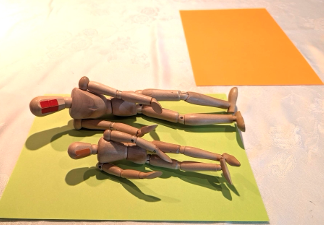

I used multimodality CA in a detailed planning meeting prior to the interview, to explain, demonstrate and provide evidence-based reasons for recruiting aids in interview. Any barriers to recruiting material objects in interview were resolved at that point. We used two different sized mannequins to represent her grandfather and herself (A), and coloured paper to represent a bed and a sofa (B) involved in the allegation.

All communication aids were introduced in a non-leading, systematic and orderly manner, with the VP typically using a word or phrase first before each successive aid was recruited. Aid use was managed by the police officer and myself, where the VP was given clear step-by-step aid-related embodied instructions, enabling her to ‘show’ what happened in a sequential manner. Neither the police officer nor I told her WHAT to say: we had shown her HOW to communicate in a manner that was aligned with her mode of communication. Her use of embodied actions (i.e., placing of the objects, positioning them in relation to each other) comprised the second part of the adjacency pair, enabling her to communicate various sub-happenings in the allegation (C).

We used colour, size and manipulation of 3D objects in that manner, to render her account more linguistically accessible.

Explanation and evidence to court

I wrote a comprehensive report for court, analysing her understanding and use of aids in assessment, drawing parallels with how they were used in interview and how they could be used in cross examination if and when the case proceeded to that part of the trial. The court was able to view the visually recorded interview including the non-leading, systematic and orderly manner in which the aids and embodied instructions were given, to satisfy itself that the evidence thus produced was legally admissible. Because aid selection, introduction and management were carried out in a transparent manner, together with robust analysis of her communication and interaction abilities, any possible future accusations of bias would be unfounded.

Not only did the aids enable her to communicate evidence that she was previously unable to do in accordance with her right to a fair trial, but they also enabled the court to understand the timeline and positions of the parties involved. The defendant offered an early guilty plea on viewing the video recorded evidence-in-chief, thus eliminating the need for additional court time. While the verdict is immaterial in relation to me as a practitioner-researcher, it was satisfying to appreciate the real-world application of CA in the justice system.

Dr Tina Pereira is a highly experienced HMCTS Appointed Intermediary who has worked with vulnerable people in criminal and family courts, mostly in the West Midlands for several years. She is also an accredited Registered Intermediary with the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). She was on the MoJ’s intermediary training team for some years and currently serves on their Registered Intermediary Reference Team, which provides corporate intermediary related work.

References

HRA. 1998. Human Rights Act: The Articles. In: UK Parliament ed. Right to a fair trial. London: The National Archives.

Ministry_of_Justice. 2024. Ministry of Justice Witness Intermediary Scheme: Information about Registered Intermediaries as part of the Ministry of Justice Witness Intermediary Scheme. [Online]. London: Ministry of Justice Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ministry-of-justice-witness-intermediary-scheme#:~:text=Registered%20Intermediaries%20conduct%20an%20assessment,therapy%2C%20teaching%20and%20social%20work. [Accessed: 19-06-24].

Peirce, C. S. 1893-1913. What is a sign? In: Project, P.E. ed. The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical writings. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 4-10.

YJCEA. 1999a. Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act. In: UK Parliament ed. Special Measure 30: Communication Aids. London: UK Parliament,.

YJCEA. 1999b. Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 London: