The two sentences “The baby cried. The mommy picked it up” are Harvey Sacks’s vivid example of how descriptions imply relationships, attitudes, behaviours and a whole host of physical, social and perhaps moral attributes. As Sacks pointed out, we all unconsciously see “the mommy” as being the mommy of that baby, and having the right or indeed the obligation to pick it up. But where do the two sentences come from? Jack Joyce takes up the story…

“The baby cried. The mommy picked it up” is a tried and tested illustration of Sacks’ assembling the apparatus of what he called Membership Categorisation Analysis (MCA) to analyse categories-in-use. A cursory search on Google Scholar reveals 743 citations using the quote. They range from membership categorisation analysis textbooks, studies of storytelling, studies of child-talk, studies of humour, clinical communication studies, countless PhD theses, to the Wikipedia page for Conversation Analysis.

Its immediate recognisability and accessibility for describing MCA is why Linda Walz, Tilly Flint and I decided to use it in our upcoming book chapter (Identity and Membership Categorization Analysis – out in the Handbook of CA in a couple years’ time!). We sent off our chapter to the editors, only to receive spine-chilling email: “Routledge has asked that one of the authors go to the original publisher and seek copyright clearance”. But who to ask? Where did the quote actually come from?

What makes this pair of sentences so evocative, anyway?

The example beautifully and plainly captures different aspects of how we may recognise categories and their predicates in everyday talk—and how we might be inclined to see the mommy as accountable for comforting a crying baby.

It’s why so many authors have used and reused the example in their work. Sacks’ analysis of the two sentences describes how the action of the baby ‘crying’ is responded to by the ‘picking up’ action by the mommy. The hearer’s maxim explains how the hearer may interpret ‘baby’ and ‘mommy’ as being a standard relational pair and belonging to the same category device ‘family’, which Sacks terms collection R (rights and responsibilities) as opposed to collection K (knowledge). The sentences illustrate the rules of application: economy (a single category is sufficient to describe a person) and consistency (categories used proximally can be heard as belonging to the same device). Sacks also explains the viewer’s maxim whereby activities (e.g. ‘crying’/’picking up’) may be bound to members of a category (e.g. ‘baby’/’mommy’).

Time and time again we see writers using Sacks’ illustration to exemplify MCA — a nifty short-cut to package a description of the MCA approach. Often it’s no more than just that shortcut, but people have also engaged with it in a more critical way. Some authors question the social norms drawn on, if inferring the ‘mommy’ as related to the baby. Lakoff’s (2000) analysis, for example, explores the consequential relationship of the two sentences comparing ‘picking it up’ to ‘ate a salami sandwich’, and of course Schegloff’s (2007) tutorial on membership categorization analysis explaining that observations which may assume a relationship between the ‘mommy’ and ‘baby’ (or are based on other assumptions) “steer analysis into dangerous, shallow waters” (p. 465). Of course, as any MCA researcher will remind you, MCA does not treat categories as static and decontextualised, but as constituted in the local context.

Tracking down the source

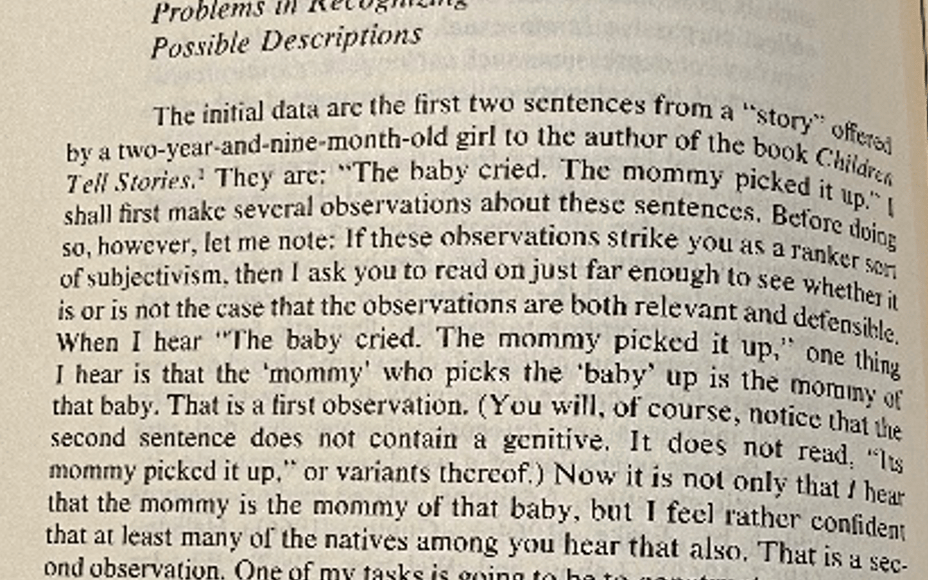

Although most famously used throughout Lectures on Conversation (1992), Sacks first published the quote in his On the Analyzability of Stories by Children in John Gumperz and Dell Hymes’s edited collection on the Ethnography of Communication (1972). In Sacks’ words “the sentences we are considering are after all rather minor, and yet all of you, or many of you, hear just what I said you heard, and many of us are quite unacquainted with each other. I am, then, dealing with something real and something finely powerful” (1972, p. 332)

Although most famously used throughout Lectures on Conversation (1992), Sacks first published the quote in his On the Analyzability of Stories by Children (1972) in Gumperz and Dell Hymes’ edited collection on the Ethnography of Communication. In Sacks’ words “the sentences we are considering are after all rather minor, and yet all of you, or many of you, hear just what I said you heard, and many of us are quite unacquainted with each other. I am, then, dealing with something real and something finely powerful” (1972, p. 332). Tracking down the source

I assumed the 1972 chapter would be the end of the trail but upon closer inspection I noticed a footnote referencing the quote to a book analysing children telling stories by Evelyn Goodenough Pitcher and Ernst Prelinger (1963). Pitcher and Prelinger’s book collected the stories of 137 children in the late 1950s and emphasises the value of analysing how children understand the world around them, their emotional states, and their interpersonal relationships.

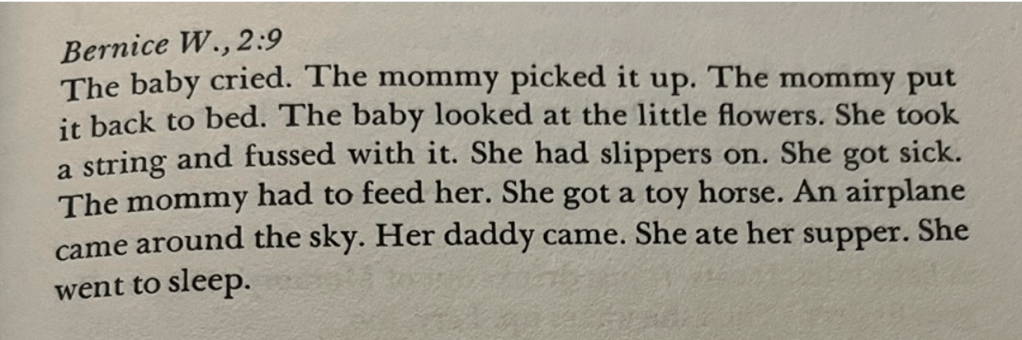

I assumed the 1972 chapter would be the end of the trail but upon closer inspection I noticed a footnote referencing the quote to a book analysing children telling stories by Evelyn Goodenough Pitcher and Ernst Prelinger (1963). Pitcher and Prelinger’s book collected the stories of 137 children in the late 1950s and emphasises the value of analysing how children understand the world around them, their emotional states, and their interpersonal relationships. This is where we find the origin of our quote. A 2-year-old named Bernice W told a story and from that innocuous story, a whole programme of research into culture-in-action was born. In Sacks’ words “the sentences we are considering are after all rather minor, and yet all of you, or many of you, hear just what I said you heard, and many of us are quite unacquainted with each other. I am, then, dealing with something real and something finely powerful” (1972, p. 332).The sentences are famously used throughout Lectures on Conversation (1992), but Sacks first published the quote in his On the Analyzability of Stories by Children (1972) in Gumperz and Dell Hymes’ edited collection on the Ethnography of Communication. Buried in a footnote next to the quote is a reference to a book by Evelyn Goodenough Pitcher and Ernst Prelinger (1963) – a collection of children’s stories – and here is where we find the origin.

This is where we find the origin of our quote. A 2-year-old named Bernice W told a story and from that innocuous story, a whole programme of research into culture-in-action was born.

Could I delve further? My excitement at finding the original quote was short-lived when I realized that the book’s publisher had been out of business for over 20 years. Undeterred, I tried to reach out to the authors, only to come across their obituaries—Evelyn Goodenough Pitcher passed away in 2004, and Ernst Prelinger in 2021. Both obituaries speak warmly of their character, highlighting how they “bettered the lives of hundreds of people”, acknowledging their prolific body of work across psychology, and both mention the 1963 study on children’s storytelling and how it was inspired by Pitcher’s own children.

It would have been wonderful to have found out more about Pitcher and Prelinger: how their book was received, how they developed it, and what further work they did thereafter. Sadly that is denied us. But one of the items in their collection has been the touchstone for a flourishing research tradition with ramifications well beyond children’s stories.In Sacks’ words “the sentences we are considering are after all rather minor, and yet all of you, or many of you, hear just what I said you heard, and many of us are quite unacquainted with each other. I am, then, dealing with something real and something finely powerful” (1972, p. 332).

Gumperz, J. J. & Hymes, D.(1972). Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication. Holt, Rinehart and Winston

Pitcher, E. G. & Prelinger, E. (1963). Children Tell Stories: An Analysis of Fantasy. International Universities Press

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation: Volume I and II. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). A tutorial on membership categorization. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(3), 462-482.